Overview

Articular cartilage is a highly organized tissue that lines the surface of our joints. It is white, smooth, shiny, and forms the gliding surface of the knee. Injury to articular cartilage can be broadly classified as traumatic or degenerative. A traumatic injury to cartilage often creates a focal cartilage defect with normal surrounding cartilage while degeneration of articular cartilage with age leads to diffuse loss of cartilage and arthritis. An acute twisting or contact injury to a knee is likely to create a focal articular cartilage injury while slow gradual onset of pain over years is likely to be degeneration of articular cartilage or arthritis. Symptoms of articular cartilage injury include pain, swelling, and mechanical symptoms (locking and catching) of the knee.

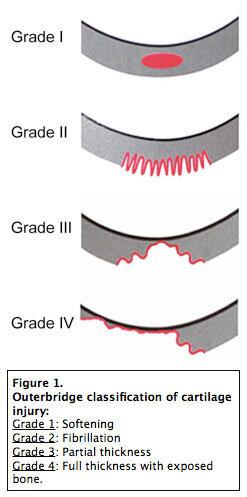

Figure 1

Figure 2

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of an articular cartilage injury begins with a physical exam to determine range of motion, swelling, and areas of tenderness. X-rays are critical to assess for arthritis and knee alignment issues. An MRI is ordered to assess the condition of the cartilage throughout the knee. At USC the radiologists use a 3 Tesla MRI machine to provide fine detail of articular cartilage.

Treatment of Articular Cartilage Injury

Treatment of articular cartilage injuries depends on the size of the lesion, location of the lesion, and whether the injury to the cartilage is focal or diffuse. Also important is the level of symptoms felt in the knee. If symptoms are mild or minor, certainly a trial of rest and rehabilitation is warranted prior to surgery.

Non-Operative Treatment

Cartilage injury in the knee is first treated conservatively with rest, ice, anti-inflammatories, and limitation of impact activities. Physical therapy to strengthen the knee can also be beneficial. If the knee remains symptomatic despite rest and rehabilitation for several months, a surgical discussion is warranted. Surgery is often indicated for the knee with an articular cartilage injury that remains painful and swollen with mechanical symptoms despite optimal nonoperative treatment.

Surgical Treatment

Cartilage injuries are described and classified based on the location of injury, size of the injury, and the depth of the injury. The type of surgery necessary largely depends on the aforementioned factors.

In addition to the characteristics of the articular cartilage lesion in the knee, the following factors are considered when planning a surgery for articular cartilage:

- STABILITY: Instability of the knee can be a precipitating factor for cartilage injury and must be treated in conjunction with appropriate surgery for the cartilage lesion. For example, an ACL deficient knee is treated with an ACL reconstruction at the time of the cartilage restoration surgery to restore stability to the knee and protect the articular cartilage repair.

- ALIGNMENT: Malalignment can be a risk factor for articular cartilage injury. Malalignment off the knee causes weight to be distributed unevenly across the inner (medial) or outer (lateral) aspect of the knee. If the cartilage lesion is in the knee compartment bearing a disproportionate amount of body weight, the knee is treated with a knee alignment correcting procedure (knee osteotomy) in conjunction with cartilage restoration procedure.

- MENISCUS: Meniscus injuries can coexist with articular cartilage injuries. Removal of small pieces of torn meniscus, meniscal repair, and even meniscal transplantation are performed if necessary, during articular cartilage restoration surgery.

Knee Arthroscopy/Debridement

Small articular cartilage lesions that do not involve the full thickness of the cartilage (grade 2 or 3) can cause mechanical symptoms and swelling. Knee arthroscopy with debridement of the lesion removes unstable flaps of cartilage and loose bodies and can result in symptomatic improvement in the knee, especially when surrounding cartilage is normal. Weight bearing is allowed with crutches immediately and return to sports can be expected after physical therapy for 6-8 weeks.

Micro-Fracture

When an articular lesion extends down to bone, it is termed full thickness or grade 4. Microfracture is considered by many sports medicine knee surgeons as a ‘first line’ cartilage restoration procedure, particularly for small lesions less than 2 cm2. This surgery is performed arthroscopically and involves the following steps:

Microfracture Surgery Steps

- 1 – Removal of loose cartilage flaps to create a lesion that is ‘well shouldered’

- 2 – Removing the calcified cartilage layer to expose the subchondral bone

- 3 – Penetration of the bone with a specialized instrument to access the bone marrow

- 4 – The bone marrow forms a clot which fills in the defect in the articular cartilage with scar cartilage.

- 5 – Optional: Application of morcellized cartilage (Biocartilage) to serve as a matrix followed by fibrin glue

Recovery After Microfracture Surgery

Surgery is performed as an outpatient. After the microfracture is formed, the knee is immobilized in a knee brace and the patient is instructed to be strictly non-weightbearing on the operated leg for a full 6 weeks. The knee is treated with a continuous passive motion machine (CPM) for 6 weeks. After 6 weeks of healing, the brace is removed, and strengthening starts. Return to sport is expected at 4-6 months. Surgery is successful in returning patients to impact sports in 2/3 of cases.

Osteochondral Autograft Transfer (OATS)

Osteochondral autograft transfer is indicated for cartilage lesions from 2 cm2 to 4 cm2 or lesions that have failed microfracture surgery. Osteochondral autograft transfer, also called OATS or mosaicplasty, involves harvesting cylinders of cartilage and bone from areas of the knee that do not bear much weight (the periphery of the knee). These cylinders are then press fit into the cartilage lesion on the weightbearing surface of the knee. The donor sites are then backfilled with synthetic plugs or left to heal on their own.

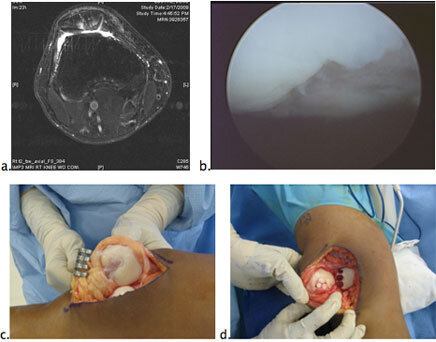

Figure 3

Figure 3. OATS Procedure:

- MRI picture of full thickness (grade 4) loss of cartilage on the patella.

- Arthroscopic photo confirming the loss of cartilage on the patella

- Open exposure of the patella showing a 2 x 2.5 cm grade four cartilage lesion

- After resurfacing with three osteochondral autograft plugs. The harvest sites have been backfilled with synthetic plugs.

Recovery After Oats Procedure

Surgery is performed as an outpatient. After the OATS is performed, the knee is immobilized in a knee brace and the patient is instructed to be strictly non-weightbearing on the operated leg for a full 6 weeks. The knee is treated with a continuous passive motion machine (CPM) for 6 weeks. After 6 weeks of healing, the brace is removed, and strengthening starts. Return to sport is expected at 4-6 months. The main concern and limitation of OATS procedure involves the limited amount of cartilage tissue that can be harvested without causing significant donor site morbidity. In essence, the procedure ‘robs Peter to pay Paul’ so the size of lesion treatable by OATS maxes out at 4 cm2.

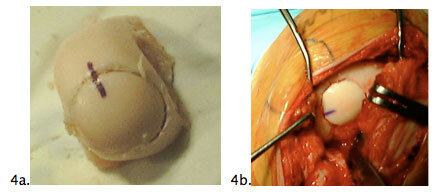

Osteochondral Allograft Transfer

Large defects 4 cm2 or greater in the weightbearing cartilage of the knee are very difficult to treat. These lesions are often not ‘well shouldered’ and therefore don’t respond to microfracture. In addition, these lesions cannot be treated with autograft OATS because not enough cartilage is available from the patient’s knee for transfer to fill the entire defect. In this difficult clinical scenario, the knee with the large articular cartilage lesion is often treated with allograft OATS (osteochondral allograft transplantation).

Osteochondral allograft transplantation usually involves transfer of a large, fresh bone/cartilage plug to the weightbearing surface of the femur. This plug is obtained for an organ donor that is matched to the patient based on knee size on x-ray. The donor femur is harvested, the donor and graft are carefully screened for any diseases and the cartilage transplant then occurs prior to 14 days to preserve the viability of the cartilage cells. This procedure, therefore, cannot reliably be scheduled in advance due to the limited availability of matched donors.

The procedure is performed through an open approach to the knee and therefore usually requires a one night stay in the hospital. The exact area of cartilage that is missing on the patient’s femur is mapped out and harvested as a cylinder of cartilage and bone. This cylinder of donor cartilage is then press fit into the patient’s femur, completing the cartilage transplant. Rehabilitation after osteochondral allograft transfer is similar to that of autograft OATS but at a slightly slower pace due to the necessity of incorporation of the allograft tissue.

Success of this Procedure is Likely as Long as

- There is no limb malalignment.

- There is no knee instability

- There is no diffuse arthritis or cartilage damage on the tibia (bipolar lesion)

Figure 4. Osteochondral Allograft transfer. A large cylindrical plug is harvested from a cadaveric femoral condyle (4a) and implanted in the matched position in the cartilage defect through an open approach.

Figure 4

Cell-Based Therapies

ACI or autologous chondrocyte implantation was originally described in 1994 in Scandinavia. This procedure involves a simple arthroscopy to harvest cartilage cells from the knee. The cartilage cells are then sent to a laboratory where they are multiplied. The cells are then implanted through an open surgery underneath a patch sewn to the native cartilage. Although ACI is available in the United States, significant improvements have been made to the technique since its original description in 1994; these include implantation of cartilage cells on matrices or scaffolds rather than underneath a patch. Because the FDA trial process is extremely stringent, these newer cell based therapies are still considered experimental in the United States.

Summary

Symptomatic articular cartilage lesions are a difficult problem to treat. Microfracture, OATS, and allograft OATS are successful in restoring function in the majority of knees, but not all. Rehabilitation is prolonged and always involves a period of complete non-weightbearing of the knee and a CPM machine to bend the knee for at least 6 weeks. Success is dependent on not only resurfacing the cartilage successfully, but also on addressing associated meniscal problems, limb malalignment, and knee instability.