Overview

A ligament is a rope-like structure in the body that connects two bones, thereby controlling the movement and stability across the joint. In the elbow, one of the most important ligaments is the ulnar collateral ligament. This ligament provides considerable and important strength on the inner aspect of the elbow while throwing. The ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) traverses the inner aspect of the elbow from the ulna to the humerus.

Figure 1, below, shows the three bands in the UCL. The anterior band of the UCL is the arm’s primary restraint from valgus stress to the elbow. During throwing, a tremendous valgus stress is placed across the elbow joint. Studies have shown that pitching a baseball generates a valgus force at the elbow estimated at 290 Newtons, resulting in an angular velocity in excess of 3000 degrees per second.

Figure 1

These high forces across the inner aspect of the elbow occur in throwing during the late cocking and early acceleration phase of throwing (Figure 2, below). The tremendous force and rotational velocity generated by pitching and throwing place stress on the ulnar collateral ligament. The forces generated at the elbow during throwing can exceed the tensile strength of the UCL. This force can cause failure of the ligament all at once (acute rupture of the UCL) or more commonly a slower, attritional rupture of the ligament due to microtrauma and repetitive stress. The repetitive stress on the ligament leads to lengthening, tearing and attrition of the UCL which in turn causes medial (inner) elbow pain, decrease in velocity of throwing, and an inability to throw effectively.

Symptoms

Most commonly, an UCL tear presents with a gradual onset of medial elbow pain due to repetitive stresses on the ligament; this is termed a chronic UCL tear. Occasionally, throwing athletes may experience a sharp “pop” or develop sharp pain along the inside of the elbow joint on one particular throw; this is termed an acute UCL tear. Either way, the tear in the ligament leads to a decrease in velocity, pain while pitching, and lack of control. Occasionally, the ulnar nerve, which runs very close to the UCL, can be stretched, leading to numbness and tingling in the small and ring fingers.

While the instability and pain in the elbow resulting from a tear of the UCL may inhibit the ability to participate in throwing sports, it is rare that symptoms occur during activities of daily living or non-throwing sports. Many non-throwing athletes and non-athletes with UCL tears can be treated without surgery.

Diagnosis

A tear of the UCL is diagnosed in the following fashion:

- History: The patient will often report gradual or sudden onset of medial elbow pain with throwing, a decrease in velocity. These symptoms have usually been unresponsive to rest and rehabilitation.

- Physical Examination: The physician will check range of motion of the elbow, check for tenderness along the ligament and ulnar nerve (palpation), and perform several stress tests to provoke pain and instability in the elbow (e.g. milking maneuver, moving valgus stress test, valgus stress test at 30 degrees)

- Radiographs: X-rays will be performed to look for chronic changes associated with throwing such as osteophytes (bone spurs) and avulsion fractures. The doctor also may perform stress x-rays during which lead gloves are used by the examiner to apply a valgus stress to the inner aspect of the elbow to confirm that the UCL is deficient.

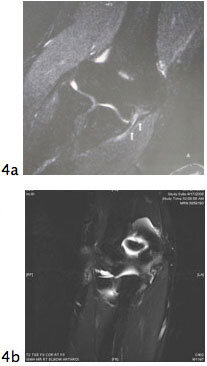

Figure 3. Stress x-rays showing opening of the medial side of the elbow joint in a patient with an ulnar collateral ligament rupture - MRI: The MRI is a powerful test that is a cornerstone of diagnosis in throwing related elbow injuries. Often it is performed with an intra-articular injection of contrast to increase the detail observed in the area of the UCL. An MRI is not 100% sensitive or specific and the results are occasionally not conclusive. That is, it is very common for the radiologist to state that there is a ‘partial tear of the UCL.’

Figure 4A and 4B show distal and proximal tears of the UCL, respectively.

Figure 4

Treatment

NON-SURGICAL TREATMENT

Initial treatment of an ulnar collateral ligament strain or partial rupture in a pitcher is non-operative. The goal is to see if the pitcher or player can return back to throwing without surgery. Treatment consists of an initial period of rest without throwing. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications (alleve/advil, etc.), ice, and local modalities can limit pain and swelling. After inflammation in the elbow has decreased, the pitcher will physical therapy designed at strengthening the elbow. Once the elbow is strong and there is no inflammation, a gradual return to throwing is initiated. The period of nonoperative treatment for a ‘strain’ of the ulnar collateral ligament can last 6-12 weeks.

If the pitcher has recurrent pain and swelling despite adequate and prolonged nonoperative treatment of the elbow it is in indication that they may not be able to pitch without reconstruction of the ligament (surgery). Because the period of recuperation is so prolonged (1 year) after reconstructive surgery of the ulnar collateral ligament, a concerted effort at rehabilitation is almost always warranted. The purpose of the physical therapy is to strengthen the muscles around the elbow to compensate for the torn ligament. When nonoperative treatment fails and a throwing athlete desires return to sport, surgery to reconstruct the ligament is usually indicated. In addition, an MRI which shows a very severe tear (complete) of the UCL, the period of nonoperative treatment is sometimes bypassed as there will be little chance of returning a player with this type of injury back to throwing without surgery.

Figure 5

Figure 6

SURGICAL TREATMENT

Surgical reconstruction of the ulnar collateral ligament was initially described by Jobe et al in Los Angeles, California. The surgery involves replacing (reconstructing) the ligament with a tendon graft and is nicknamed ‘Tommy John Surgery’ after the initial major league pitcher that had the procedure. Since the advent of the surgery there have been considerable modifications to the technique to decrease its invasiveness and improve the technique.

Dr. Gamradt trained at the Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS) in New York and uses the ‘docking technique,’ developed by Dr. David Altchek from HSS, team physician for the New York Mets. The procedure is conducted in the following fashion:

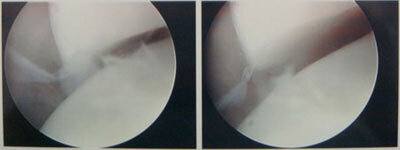

- Routine arthroscopy of the elbow to address any associated intra-articular pathology.

Figure 5. Arhroscopic valgus stress test to show opening of the medial elbow joint in the setting of a torn UCL in a 20 year old pitcher. - Harvest of a small, expendable tendon from the wrist called the Palmaris tendon to use as a graft to replace the ulnar collateral ligament. If the Palmaris tendon is not available, a gracilis graft from the leg is used (a small hamstring tendon that is commonly used for ACL reconstruction).

Figure 6A and 6B: harvest of the Palmaris tendon through a small incision in the wrist crease. - After harvesting the graft and completing the arthroscopy, the muscle on the inner aspect of the elbow (flexor pronator) is split along its fibers to expose the native ligament

- After exposure of the native ligament, two small tunnels are drilled in the ulna for graft passage at the exact location of the native ligaments insertion on the ulna (the sublime tubercle)

- The tunnel in the humerus is drilled slightly larger to allow both limbs of the tendon graft to be docked into the tunnel.

Figure 7. Tunnels drilled and ready for graft passage. - The native ligament is then repaired and the new UCL graft is placed through the tunnels in the ulna.

- The graft is then tensioned, docked into the tunnel in the humerus and secured tightly thereby completing the reconstruction.

- Routine transposition of the ulnar nerve is not performed. Transposition of the ulnar nerve used to be a routine part of UCL reconstruction, but now it is only performed in those players with significant nerve symptoms (numbness and tingling preoperatively).

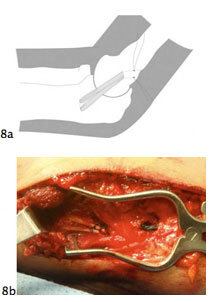

Figure 8A. Schematic of Docking Technique for UCL reconstruction from Altchek et al. Figure 8B. Final graft construct in a 20 year old college pitcher.

Figure 7

Figure 8

What to Expect

- Surgery is performed as an outpatient under regional (nerve block) anesthesia with or without general anesthesia.

- After surgery, a plaster splint is placed on the arm to immobilize the elbow for 10 days to allow the soft tissues to heal.

- After surgery while in the splint, fingers may become swollen and slight numbness is normal. To minimize these symptoms, elevate the arm and move the fingers frequently.

- After 10 days, the splint is removed and a removable hinged elbow brace is applied that will allow the elbow to be moved within a safe range of motion. This range of motion is increased each week in a protected fashion until the brace is removed at 6 weeks. During this time grip strength and wrist range of motion is encouraged.

- At week 6 gentle elbow strengthening is begun and full range of motion is achieved with the help of the physical therapist.

- Progressive strengthening of shoulder and elbow is encouraged until month four (16 weeks post-surgery)

- A very light tossing program is begun at that time. Progressive physical therapy and an interval throwing program usually returns a pitcher to competition somewhere between 9 and 12 months. Continued improvement in the elbow can be noticed all the way to 24 months after the operation.

- The lengthy and slow recovery is needed for complete healing and incorporation of the graft. Attempts at accelerated rehabilitation after this operation have shown an increased risk of graft failure.

- Success rate of the operation is high. 80-90% of pitchers return to their previous level of competition.

- Risks include bleeding, infection, reoperation, nerve damage (ulnar nerve), elbow stiffness, elbow pain, and a potential that the player may fall into the minority of pitchers in whom the surgery is not effective at restoring their ability to pitch.

Do I Need UCL Reconstruction Surgery?

The vast majority of patients who need UCL reconstruction surgery (‘Tommy John Surgery’) are competitive pitchers and other throwing athletes. Because of the extremely lengthy rehabilitation process and a success rate that is not 100%, a period of rest followed by non-operative treatment is commonly recommended to make absolutely certain that the surgery is indicated and that the player cannot return to competition without surgery.

An MRI finding of an imperfect UCL (e.g. partial tear) does not immediately necessitate surgery either. An adage among surgeons who care for baseball players is: ‘operate on the patient, not the MRI.’ A complete tear in a pitcher, however, is unlikely to respond to nonoperative treatment.

If non-operative treatment of a completely or partially torn UCL fails, then surgery certainly is the best option should the pitcher or throwing athlete desire a return to competition. Done correctly, the surgery is a safe and effective way of returning a large majority of players with this injury back to competition, albeit after the lengthy rehabilitation process.